I came to Greece because nineteenth century British culture was so strongly influenced by Greek culture that I wanted to see the other side of the story–to learn about Greek perspectives on Anglo-Hellenic relations, both then and now.

From the Age of Enlightenment on, the British saw themselves as the natural heirs of Greek civilization, an attitude that sometimes seems to continue even today, as witness a 2011 exhibit of British art at King’s College London titled “‘A brighter Hellas’: rediscovering Greece in the 19th century,” or the British Museum’s controversial refusal to restore the Parthenon statues to their homeland.

On the other hand, some British–especially those who were themselves marginalized in one way or another–critiqued their countrymen’s casual looting of Greek remains. Here’s Byron, writing in 1815 about the Acropolis:

Look on this spot—a nation’s sepulchre!

Abode of gods, whose shrines no longer burn.

E’en gods must yield—religions take their turn:

‘Twas Jove’s—’tis Mahomet’s; and other creeds

Will rise with other years, till man shall learn

Vainly his incense soars, his victim bleeds;

Poor child of Doubt and Death, whose hope is built on reeds.

(from Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Canto III, 1812-1818)

Byron’s explicit critique of the Ottoman Empire carries an implicit warning to the British–as well as uncanny shadows of the religious and nationalist conflicts whose ravages we just witnessed in the Balkans. And later in the poem, Byron condemns Lord Elgin (who in the first decade of the nineteenth century carted off much of the statuary from the Acropolis and shipped it back to Britain ) as a plunderer:

Dull is the eye that will not weep to see

Thy walls defaced, thy mouldering shrines removed

By British hands . . .

“Elgin’s Marbles” have been a point of contention between Britain and Greece ever since.

I’ve been fascinated to see how often the British pop into the lectures given by our Greek guides. On our first day in Athens, we were shown the house where Byron lived. At the Beehive Tomb in Mycenae, we learned that the columns that originally decorated the tomb are now in the British Museum, because (as our guide Roula put it) “Lord Elgin also . . . ahem, paid his respects in Mycenae.” In Olympia, as Deb mentioned in an earlier post, we learned that the Germans have restored the relics they expropriated from Greece–but the Brits have not followed suit.

On the Acropolis in Athens, Lord Elgin holds the dubious distinction of being the foreigner mentioned most often in official representations of the site’s history. By the Erechtheion, for example, a Ministry of Culture placard informs visitors that “In the first years of the 19th century Lord Elgin of Britain carried off the third caryatid from the west . . . and the column of the northeast corner of the building. Today they have been replaced by copies.”

And when touring the astonishing new Acropolis museum, we heard even more about Lord Elgin. The museum draws visitors’ attention to his violent expropriation of Greek heritage by exhibiting “ocular proof” of his destructive methods. High on a wall hang replicas of the Parthenon’s freize, with a placard informing visitors that many of the originals were taken from Greece by Elgin and are still displayed by the British Museum. Directly below the frieze sits a rough block of stone.

Roula explained its purpose: as part of the original wall that supported the statuary, this stone still bears the marks of successive generations of depredation: first by the Turks and then of the British. The Ministry of Culture wants museum visitors to be able to see the physical scars left by the crowbars that brutally prised the statues off of the Parthenon, and a short animated video on a screen just below the frieze shows a crowbar in action, separating frieze from stone.

Roula explained its purpose: as part of the original wall that supported the statuary, this stone still bears the marks of successive generations of depredation: first by the Turks and then of the British. The Ministry of Culture wants museum visitors to be able to see the physical scars left by the crowbars that brutally prised the statues off of the Parthenon, and a short animated video on a screen just below the frieze shows a crowbar in action, separating frieze from stone.

This mute stone block bears silent witness to centuries of Anglo-Hellenic relations–but only because the museum’s curators deliberately staged a display that speaks to present day political and cultural relations as much as it does to the past.

As for the British, if you watch the British Museum’s official advert on the Elgin Marbles–which are now, by common consent, renamed the Parthenon Marbles–you might well think that Britain still considers itself the true inheritor of “the grandeur that was Greece and the glory that was Rome.”

But as always, more nuanced perspectives also exist. I’ll let John Keats have the last word on the British confrontation with Ancient Greece:

Such dim-conceived glories of the brain

Bring round the heart an undescribable feud;

So do these wonders a most dizzy pain,

That mingles Grecian grandeur with the rude

Wasting of old Time — with a billowy main —

A sun — a shadow of a magnitude.

(On Seeing The Elgin Marbles, March 1817)

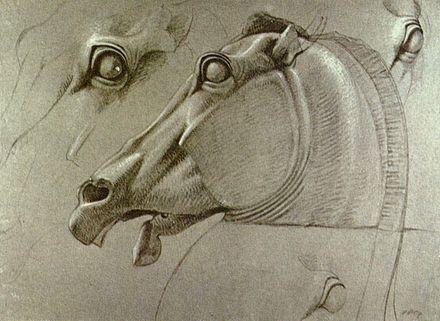

Benjamin Robert Haydon, “Head of the horse of Selene, from the east pediment of the Parthenon” (Black chalk, heightened with white, on grey paper; British Museum, London).

Jenna